Many insects depend on heritable bacterial endosymbionts to supply essential nutrients missing from their diets. A recent study reveals that genomes of these symbiotic bacteria shrink dramatically over time, with some in planthoppers setting a new record for the smallest non-organelle genome discovered.

Essential Role of Endosymbionts in Sap-Feeding Insects

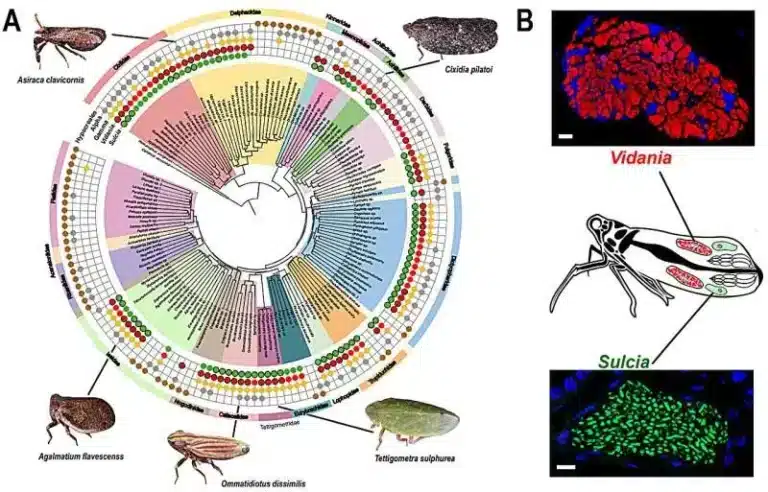

Sap-sucking insects like planthoppers and cicadas rely on endosymbiotic bacteria for survival. Plant sap lacks key amino acids and vitamins, so these insects have co-evolved over hundreds of millions of years with bacteria that provide them. Sulcia and Vidania, two such endosymbionts, have partnered with planthoppers for over 260 million years, residing in specialized abdominal cells.

Record-Shattering Genome Sizes

Researchers sequenced and compared 131 complete symbiont genomes—63 Sulcia and 67 Vidania—from 149 planthopper species. Sulcia genomes range from 137,729 to 180,379 base pairs (bp), while Vidania genomes span 50,141 to 136,554 bp. Several Vidania genomes eclipse prior records, including Nasuia in leafhoppers (at least 107.8 kb), earlier Vidania strains (at least 108.6 kb), and Tremblaya in mealybugs (at least 139 kb).

Researchers note, “The reconstructed Sulcia genomes ranged in size from 137,729 bp to 180,379 bp, and Vidania ranged from 50,141 bp to 136,554 bp.”

Minimal Genes for Host Survival

These ultra-compact genomes retain only essential genes, primarily for synthesizing phenylalanine, a critical amino acid for the host. Loss of genes tied to other cellular functions renders the bacteria heavily reliant on their insect hosts, resembling organelles.

Convergent Evolution Across Lineages

Two planthopper superfamilies show convergent evolution, with Vidania strains VFSACSP1 (50,141 bp) and VFMALBOS (52,460 bp) developing independently. Genetic analysis confirms both encode phenylalanine biosynthesis pathways, while losing those for six other amino acids.

The researchers state, “Notably, the extremely reduced state represented by these two genomes has evolved independently in two superfamilies separated by ~263 million years of evolution. Despite their independent origins, these genomes exhibit striking similarity in gene retention patterns and organization compared to their common ancestor, which must have had a genome approximately three times their size.”

Factors Driving Genome Reduction

Evolutionary pressures explain the shrinkage, including strong mutation and deletion rates, lack of recombination, no gene acquisition opportunities, and genetic drift from transmission bottlenecks. Non-essential genes erode gradually, per population-genetic theory like Muller’s ratchet.

Further reductions occur when hosts gain complementary symbionts, face ecological shifts, or integrate functions themselves. While Vidania holds the current smallest bacterial genome record, more discoveries in other insects may follow. These findings illuminate organelle evolution, such as mitochondria, and cellular life’s limits.

Study: Anna Michalik et al, “Convergent extreme reductive evolution in ancient planthopper symbioses,” Nature Communications (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-026-69238-x