by Terry Heick

The affect of Berry on my life–and thus inseparably from my instructing and studying–has been immeasurable. His concepts on scale, limits, accountability, group, and cautious pondering have a spot in bigger conversations about financial system, tradition, and vocation, if not politics, faith, and anyplace else the place frequent sense fails to linger.

However what about schooling?

Under is a letter Berry wrote in response to a name for a ‘shorter workweek.’ I’ll go away the argument as much as him, nevertheless it has me questioning if this type of pondering could have a spot in new studying varieties.

Once we insist, in schooling, to pursue ‘clearly good’ issues, what are we lacking?

That’s, as adherence to outcomes-based studying practices with tight alignment between requirements, studying targets, and assessments, with cautious scripting horizontally and vertically, no ‘gaps’–what assumption is embedded on this insistence? As a result of within the high-stakes sport of public schooling, every of us collectively is ‘all in.’

And extra instantly, are we making ready learners for ‘good work,’ or merely educational fluency? Which is the position of public schooling?

If we tended in the direction of the previous, what proof would we see in our school rooms and universities?

And possibly most significantly, are they mutually unique?

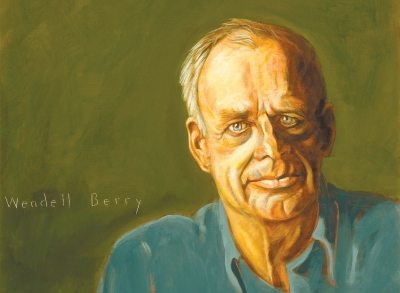

Wendell Berry on ‘Good Work’

The Progressive, within the September difficulty, each in Matthew Rothschild’s “Editor’s Notice” and within the article by John de Graaf (“Much less Work, Extra Life”), presents “much less work” and a 30-hour workweek as wants which are as indeniable as the necessity to eat.

Although I might help the concept of a 30-hour workweek in some circumstances, I see nothing absolute or indeniable about it. It may be proposed as a common want solely after abandonment of any respect for vocation and the substitute of discourse by slogans.

It’s true that the industrialization of just about all types of manufacturing and repair has stuffed the world with “jobs” which are meaningless, demeaning, and boring—in addition to inherently damaging. I don’t assume there’s a good argument for the existence of such work, and I want for its elimination, however even its discount requires financial adjustments not but outlined, not to mention advocated, by the “left” or the “proper.” Neither aspect, as far as I do know, has produced a dependable distinction between good work and unhealthy work. To shorten the “official workweek” whereas consenting to the continuation of unhealthy work is just not a lot of an answer.

The previous and honorable thought of “vocation” is solely that we every are known as, by God, or by our items, or by our choice, to a type of good work for which we’re notably fitted. Implicit on this thought is the evidently startling risk that we’d work willingly, and that there isn’t any essential contradiction between work and happiness or satisfaction.

Solely within the absence of any viable thought of vocation or good work can one make the excellence implied in such phrases as “much less work, extra life” or “work-life stability,” as if one commutes day by day from life right here to work there.

However aren’t we dwelling even after we are most miserably and harmfully at work?

And isn’t that precisely why we object (after we do object) to unhealthy work?

And in case you are known as to music or farming or carpentry or therapeutic, in case you make your dwelling by your calling, in case you use your expertise nicely and to a superb objective and due to this fact are joyful or glad in your work, why do you have to essentially do much less of it?

Extra essential, why do you have to consider your life as distinct from it?

And why do you have to not be affronted by some official decree that you must do much less of it?

A helpful discourse with reference to work would elevate a lot of questions that Mr. de Graaf has uncared for to ask:

What work are we speaking about?

Did you select your work, or are you doing it underneath compulsion as the way in which to earn cash?

How a lot of your intelligence, your affection, your ability, and your delight is employed in your work?

Do you respect the product or the service that’s the results of your work?

For whom do you’re employed: a supervisor, a boss, or your self?

What are the ecological and social prices of your work?

If such questions should not requested, then we now have no manner of seeing or continuing past the assumptions of Mr. de Graaf and his work-life consultants: that every one work is unhealthy work; that every one staff are unhappily and even helplessly depending on employers; that work and life are irreconcilable; and that the one answer to unhealthy work is to shorten the workweek and thus divide the badness amongst extra folks.

I don’t assume anyone can honorably object to the proposition, in principle, that it’s higher “to cut back hours somewhat than lay off staff.” However this raises the probability of lowered revenue and due to this fact of much less “life.” As a treatment for this, Mr. de Graaf can supply solely “unemployment advantages,” one of many industrial financial system’s extra fragile “security nets.”

And what are folks going to do with the “extra life” that’s understood to be the results of “much less work”? Mr. de Graaf says that they “will train extra, sleep extra, backyard extra, spend extra time with family and friends, and drive much less.” This joyful imaginative and prescient descends from the proposition, widespread not so way back, that within the spare time gained by the acquisition of “labor-saving units,” folks would patronize libraries, museums, and symphony orchestras.

However what if the liberated staff drive extra?

What in the event that they recreate themselves with off-road autos, quick motorboats, quick meals, laptop video games, tv, digital “communication,” and the varied genres of pornography?

Properly, that’ll be “life,” supposedly, and something beats work.

Mr. de Graaf makes the additional uncertain assumption that work is a static amount, dependably obtainable, and divisible into dependably adequate parts. This supposes that one of many functions of the economic financial system is to offer employment to staff. Quite the opposite, one of many functions of this financial system has all the time been to remodel unbiased farmers, shopkeepers, and tradespeople into workers, after which to make use of the staff as cheaply as potential, after which to switch them as quickly as potential with technological substitutes.

So there might be fewer working hours to divide, extra staff amongst whom to divide them, and fewer unemployment advantages to take up the slack.

Then again, there may be a variety of work needing to be completed—ecosystem and watershed restoration, improved transportation networks, more healthy and safer meals manufacturing, soil conservation, and so on.—that no person but is prepared to pay for. Eventually, such work should be completed.

We could find yourself working longer workdays so as to not “reside,” however to outlive.

Wendell Berry

Port Royal, Kentucky

Mr. Berry’s letter initially appeared in The Progressive (November 2010) in response to the article “Much less Work, Extra Life.” This text initially appeared on Utne.