[ad_1]

This story was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Middle. This story was made doable via the help of the U.S. Nationwide Science Basis Workplace of Polar Applications.

Rachel Feltman: For Scientific American’s Science Rapidly, I’m Rachel Feltman.

5 and a half trillion tons. That’s how a lot ice has melted out of the Greenland ice sheet since simply 2002.

On supporting science journalism

In case you’re having fun with this text, think about supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By buying a subscription you’re serving to to make sure the way forward for impactful tales concerning the discoveries and concepts shaping our world at this time.

It’s a quantity nearly too giant to wrap your head round. However in case you took that a lot water and used it to fill Olympic-size swimming pools—which maintain [about] 600,000 gallons, by the way in which—you’d have a lap pool for each particular person residing in Africa and Europe, all 2.2 billion of them.

The rationale we all know that is that for greater than 20 years, satellites have been watching and measuring the so-called mass loss from Greenland’s ice sheet—one in all solely two ice sheets on the earth. Antarctica is the opposite one.

What science doesn’t know is how the Greenland ice sheet may come aside. And that’s a very necessary query to reply, because it has a complete of 24 toes of sea-level rise nonetheless locked up in its icy mass.

A drone’s-eye view of the windswept GreenDrill camp on the Greenland ice sheet.

Jeffery DelViscio/Scientific American

Right now on the present we’re speaking to one in all our personal: Jeff DelViscio, the top of multimedia at SciAm and government producer of the podcast.

Final 12 months Jeff ventured out onto the ice sheet for a month. He went with members of a scientific expedition whose sole aim was to drill via the ice to get the rock beneath, and he’s going to inform us why that issues on the subject of Greenland and the way forward for the ice sheet.

Thanks for coming onto the present, Jeff.

Jeff DelViscio: Thanks for having me, Rachel.

Feltman: So why did you go to Greenland? What was this expedition all about?

DelViscio: This was a undertaking known as GreenDrill, and GreenDrill is based totally out of two establishments, the place there are two co-PIs—so principal investigators—who’re engaged on it: one at Columbia College and one on the College at Buffalo. And so they have pulled this undertaking collectively that was meant to enter totally different components of Greenland and selectively pattern the ice sheet to have the ability to determine what was occurring with it: its state, its well being and the way they might push the science ahead on what they perceive concerning the Greenland ice sheet and the way it’s constructed and, in the end, the way it comes aside.

From left: Allie Balter-Kennedy, Elliot Moravec and Forest Harmon relaxation on a easy, steep rock face in Kangerlussuaq, a small settlement on Greenland’s southwestern coast.

Jeffery DelViscio/Scientific American

Feltman: What was life really like on an ice sheet? Do you are feeling such as you have been ready, or have been there any surprises that got here your method?

DelViscio: I used to be completely not ready. This was my first reporting in a polar zone, and when you get there you understand {that a} massive a part of your security and well-being actually depends upon the people who find themselves there with you …

Feltman: Mm.

DelViscio: And there was a long time’ value of expertise on the market on the ice sheet, and we will discuss this, however it took a very long time to really get to the place I used to be going, and that was an entire a part of the method. However as soon as I really arrived on the ice sheet correct, I believe the primary day I used to be there, temperatures have been proper round –20 levels Fahrenheit [about –28.9 degrees Celsius].

Feltman: Wow.

DelViscio: And the primary night time I slept on it, I really was at a spot in the course of the ice sheet, at a Danish ice-coring camp, in transit over to the, the ultimate location the place the GreenDrill workforce was doing their work, they usually had these 6×6 [foot] tents known as Arctic ovens—it was not an oven inside. However these have been out proper on the ice sheet. And so they mentioned, “Nicely, camp is fairly full. You must in all probability exit and sleep in a tent as a result of you could get used to it. You’re gonna be out right here for some time.” And so I did that, and it was an actual expertise, that first night time.

DelViscio (tape): So I assume I type of requested for this. I wished to go right here and do that story. It’s advantageous [laughs]. It’s simply possibly a tough first go, however I can attempt to go to mattress, see if I can get some sleep.

That is what it’s proper now. That is good observe. There’s really a station right here, so if I actually get uncomfortable, I suppose I may go inside. That’s not gonna be the case if we hit the sphere camp.

Um, yeah, wonderful reporting work within the polar arctic. Right here we’re. Goodnight day one on the Greenland ice sheet.

DelViscio: It was about –20 exterior and possibly about 10 levels, 15 levels higher within the, within the tent, so all night time about zero [degrees F, or about –17.8 degrees C], –5 [degrees F, or about –20.6 degrees C], –10 [degrees F, or about –23.3 degrees C], and it was additionally at about 8,500 toes [2,590.8 meters] on the highest of the ice sheet …

A panoramic view of the creator’s tent (second from left) on the center of the Greenland ice sheet. Expedition member Arnar Pall Gíslason could be seen on the proper.

Jeffery DelViscio/Scientific American

Feltman: Mm.

DelViscio: Which, you recognize, you’re type of on a mountain already; it’s like being within the Rockies however on the highest of a giant, extensive ice sheet. In each route you look there’s nothing—there’s no options; there’s nothing—and also you’re simply laying on ice all night time, and it, it was painful …

Feltman: Yeah.

DelViscio: I’m not gonna lie about it; it was painful. And you’ve got a sleeping bag that’s rated at –40 levels [F, or –40 degrees C], and you’ve got a hot-water bottle that you just put in to, to attempt to heat your self up, however my face was kind of protruding of the mummy-bag gap, and I’d breathe and there would simply be ice crystals forming on my beard and face …

Feltman: Wow.

DelViscio: As I breathed out, so somewhat little bit of a tough intro. However I did query why I used to be there.

DelViscio (tape): Nicely, I made it via my first night time. I wouldn’t say it was nice—actually chilly the entire time [laughs]. That’s—robust to get comfy at any level. I don’t understand how folks do that for lengthy intervals of time. Brutal, yeah. However I made it.

DelViscio: However I did get via it, and there was a whole lot of expertise, like I mentioned, individuals who knew what they have been doing, which actually helped.

Feltman: Yeah, effectively, you talked about that getting on the market took a very very long time. How did you get there, and the place did you find yourself?

DelViscio: Yeah, so it’s a course of, and I had no concept how any of this labored earlier than I, I received on the expedition, however sometimes, the U.S. navy really flies a whole lot of the science flights as a result of there’s a little bit of historical past, and I—in my function you’ll be able to learn somewhat bit about that—as a result of the U.S. navy’s been out on the, on the ice for many years for different causes than ice-core analysis and climatology analysis however I went to a base in upstate New York, received on a giant cargo airplane …

Air Drive announcer: Within the occasion of a lack of pressurization situation, in case you’re to look over your left or proper shoulder, there’s a vertical rectangular panel on the wall …

DelViscio: Which flew to Kangerlussuaq, principally a staging location the place all of the science folks type of are available from all totally different components of the world. You kind of sit there and also you wait till the circumstances are proper so you will get onto one other cargo airplane …

A small class of Greenlandic college students and academics stand on the banks of the Qinnguata Kuussua river in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland.

Jeffery DelViscio/Scientific American

DelViscio (tape): So that is it. We’re in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, and at this time we’re delivery out to the ice.

[CLIP: Sound of a Hercules C-130 cargo plane throttling up]

DelViscio: Which then takes you and your complete crew out to, for us, a staging location, the Danish ice-coring web site I discussed, out in the course of the ice ’trigger it’s too far to go on to the location.

DelViscio (tape): Okay, right here we’re: Greenland ice sheet. That is the EastGRIP [East Greenland Ice-Core Project] Danish web site. It’s chilly. My digicam’s not loving this, however right here we’re. There’s a station behind me and the solar simply attempting to peek via. Simply got here in on the Air Nationwide Guard C-130. They’re pulling our stuff over. Right here we go.

DelViscio: When you get on that smaller airplane and, you recognize, handle all of the climate and get on the market in time, you kind of sit there and also you type of load up a smaller cargo airplane …

[CLIP: Sound of a Twin Otter cargo plane throttling up]

DelViscio: To take you yet one more step, the ultimate leg, to the GreenDrill web site, which is out within the northeast a part of Greenland—actually the center of nowhere: a whole bunch of miles in each route, there’s simply ice and also you.

[CLIP: Sound of wind blowing across the ice sheet at the GreenDrill camp]

A science lab situated beneath the Greenland ice sheet inside a Danish ice coring camp known as EastGRIP on the Greenland ice sheet.

Jeffery DelViscio/Scientific American

DelViscio: So it’s an actual manufacturing. It took about 20 flights for all …

Feltman: Wow.

DelViscio: Of the folks, logistics and kit. There’s in all probability about 20,000 kilos’ value of substances, together with the drilling gear that we needed to take.

So it takes every week simply to get there, and then you definitely’re kind of flat-out working when you really do get there; the workforce is aware of that there’s solely a lot time and there’s a closing window, so it’s type of a scramble, however it’s a lengthy scramble simply to get to there.

Feltman: And the place precisely are all these planes and kit going to?

DelViscio: So that they’re going to a very unpopulated a part of the northeast Greenland ice sheet, however it was a very necessary location, and it was picked for a motive.

Think about this kind of giant dome of ice. The way in which by which it really strikes—and it does transfer—is that snow falls on the highest and kind of compresses, then spills out throughout the ice sheet, and a part of that spill-out occurs via this stuff known as ice streams. And so they’re like a stream you’d think about within the water world, however they’re simply manufactured from absolutely strong ice, they usually’re actually flowing away from the highest of the ice sheet at a velocity that’s quite a bit sooner than the encompassing ice, so you’ll be able to really see them in satellite tv for pc information.

And so we have been positioned proper on the fringe of one thing known as the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream, which drains about 12 to 16 % of the ice sheet, so, like, principally over 10 % of the water that’s type of going out and shifting to the ocean, stepping into glaciers after which going into the ocean comes via this huge ice stream, which is basically simply this massive tongue of ice shifting sooner than the encompassing components of it.

That location is basically necessary to grasp how the ice sheet loses its mass, and in case you pattern at simply the precise level, then you’ll be able to perceive, on this actually vital portion of the ice sheet, precisely how that ice stream works when it comes to preserving the ice both rising or shrinking, and proper now it’s actually shrinking, so that they wanna perceive how these streams can play a component in pulling the ice sheet aside itself.

From left: Caleb Walcott-George, Allie Balter-Kennedy and Arnar Pall Gíslason look out over the Greenland ice sheet and the GreenDrill camp.

Jeffery DelViscio/Scientific American

Feltman: Yeah, let’s discuss extra concerning the science. What sort of experiments are occurring right here?

DelViscio: Yeah, so there’s all of this ice, proper? And up to now 60 years or so folks have gone to the Greenland ice sheet to principally pull these lengthy tubes of ice out of the ice sheet itself and use the ice as a document of local weather change as a result of ice is laid down yearly and it’s principally like a tree ring …

Feltman: Mm-hmm.

DelViscio: However in an ice sheet. And in case you pull out giant sections of it from the center of the ice sheet, you’ll be able to rise up to [roughly] 125,000 years of local weather: the snow falls, it compresses it captures the air that was above it on the time in little air bubbles, so the ice cores are these data of local weather going into the previous.

Everybody was at all times centered on the ice, for the reason that, like, ’60s: “What can the ice inform us about local weather? How can we join it as much as different data of local weather change and paleoclimate within the different components of the world?” However nobody, or only a few folks, regarded beneath it.

And the necessary half about being beneath the ice sheet is that the rock itself that’s underneath the ice sheet tells you one thing about when it’s had ice on it and when it hasn’t, and when it hasn’t is a very necessary a part of that as a result of if we’re questioning about how the ice sheet breaks up, we actually must understand how shortly that’s occurred up to now. And at this level science has little or no concept about how that really works.

So what they did was: We have been on the market with these small drills, packed up in type of containers. You’re taking the drill and also you drill all over the ice …

[CLIP: Sound of the Winkie Drill drilling through the ice sheet]

DelViscio: And also you’re not completely happy whenever you resolve it—you cease, and then you definitely maintain going, and also you pull the rock out from beneath the ice. The sport right here is to do measurements on that rock and see what it is going to let you know about when this place had ice and when it didn’t.

There’s type of an excellent quote from one of many co-principal investigators on the undertaking that actually type of summed up why they began doing this. Right here’s what he needed to say.

Joerg Schaefer: [In] 2016 was the primary examine that was led by us that reveals that you’ve got these instruments, these geochemical isotopic instruments, to interview bedrock, and the bedrock really talks to us.

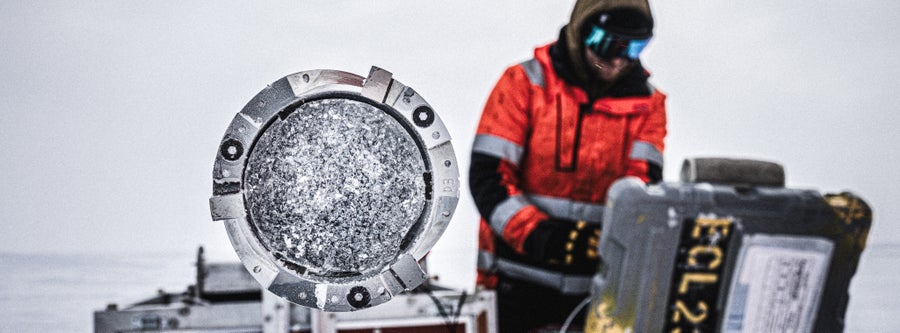

Forest Harmon, a ice and rock driller, with the Eclipse ice drill on the Greenland ice sheet in June 2024.

Jeffery DelViscio/Scientific American

Since then it’s clear to us, at the very least, that that’s a brand new department of science that’s completely vital—it’s actually on the interface of fundamental geochemical and local weather science and societal influence. It’s one in all these uncommon events that there’s direct contact between fundamental analysis and scientific influence and questions like local weather and social justice, so it’s a really—scientifically, an especially thrilling time.

[In] the identical second I need to say that every thing now we have discovered thus far may be very scary. And I type of have, [for] the primary time ever in my profession, I’ve datasets that I—take my sleep away at night time, just because they’re so direct and inform me, “Oof, this ice sheet is in a lot bother.”

DelViscio: That’s Joerg Schaefer from Columbia College.

Feltman: What was it about these datasets that he discovered so troubling?

DelViscio: Positive, so I simply talked about that lengthy ice core that they pulled from the center of the ice sheet and utilizing that as a document. Within the Nineteen Nineties a type of was pulled at a spot known as GISP2, which is the Greenland Ice Sheet Undertaking 2 web site. It was an American web site, they usually went additional than anyone else had up to now, and as soon as they received via the whole lot of that ice, about 10,000 toes value of ice, they pushed the drill farther, slammed it down into the rock and pulled some rocks out. Now, the ice core went off to be in hundreds and hundreds of different papers related to data all around the world; the rock beneath went to a freezer and received saved, and folks principally forgot about it.

Joerg Schaefer and Jason Briner of the College at Buffalo, within the early 2010s they realized that that rock may let you know one thing, and now they’d chemical instruments to research that rock in a method that it hadn’t [been] earlier than. And they also went again and received that rock, they examined it, and in 2016 they printed a paper that confirmed: at that web site in the course of the ice sheet, their chemical checks advised them that it was ice-free inside the final million years. Which means the complete ice sheet was gone.

Feltman: Wow.

DelViscio: And that was method faster than anyone thought was doable.

And in order that spurred this complete subsequent step, which was: “If we received extra of those rocks from totally different components of the ice sheet, what else will it inform us about how shortly this occurs?”

Polar information Arnar Pall Gíslason checks the horizon for polar bears via his gun scope on the Greenland ice sheet.

Jeffery DelViscio/Scientific American

Jason Briner: The mattress of the ice sheet comprises a historical past of the ice that covers it—principally the phrases, the tales of the historical past of the ice sheet. It’s a guide of knowledge down there that we need to learn if we will get these samples.

DelViscio: That’s Jason Briner. In order that was the seed of this complete factor. So in case you stick this soda straw down into the rock and also you pull it again out, you’ll be able to check a number of areas, and it may let you know, “Right here there was no ice then. Right here there was no ice then. Right here there was no ice then,” across the ice sheet as a technique to kind of check …

Feltman: Hmm.

DelViscio: The way it kind of shrinks again to its teeny-tiny state.

Feltman: And the way do you get that type of sign out of a rock?

DelViscio: It’s difficult [laughs]. It—you recognize, I wasn’t a chemistry main in, in class; I used to be a geology main. However one of many researchers within the subject, Allie Balter-Kennedy, you recognize, she has a great way of fascinated about it. Why don’t I simply pull Allie in to speak about how this sign comes into the rock?

Allie Balter-Kennedy: So there’s cosmic rays that are available from outer house always, and once they work together with rocks they create these nuclear reactions that create isotopes or nuclides that we don’t in any other case discover on Earth. And we all know the speed at which these nuclides are produced, so if we will measure them, we will determine how lengthy that rock has been uncovered to those cosmic rays—or, type of in our subject, how lengthy that rock has been ice-free. And so whenever you do this beneath an ice sheet, you get a way of when the final time the rock was uncovered and in addition how lengthy it was uncovered for, so it’s a fairly highly effective methodology for studying about instances when ice was smaller than it’s now.

DelViscio: These nuclides are the sign contained in the rock. In case you can inform how a lot of it’s within the rock and the way shortly these indicators ought to decay, in case you see jumps in that sign, you’ll be able to inform that ice was over high of it and it stopped the barrage from the universe, so it turned the sign on and off.

Feltman: Hmm.

DelViscio: And that’s kind of how they have a look at the sign, is like: “Is it on; is it off? Is it on; is it off?” And that tells you, in a method: “There was ice over high, or there wasn’t. There was ice over high, or there wasn’t.”

From left: Allie Balter-Kennedy, Arnar Pall Gíslason and behind, Caleb Walcott-George, use a hand drill to drag quick rock cores from the floor of a nunatak, an uncovered rock outcropping, on the Greenland ice sheet.

Jeffery DelViscio/Scientific American

Feltman: Wow, sure, that does sound very difficult [laughs] but additionally very cool. Did the workforce find yourself really getting what they have been after?

DelViscio: Yeah, so it was type of right down to the road. After all of the touring and all of the logistics, and there was some climate and delays, and there [were] cargo flights that couldn’t land, principally, every thing received compressed into about three weeks on the ice on the web site. That’s not an entire lot of time to do what they have been attempting to do.

It’s a spoiler alert, however in case you learn the function, you’ll hear about precisely how this occurred, however they did find yourself getting not simply one in all these samples, however two …

Feltman: Hmm.

DelViscio: From two totally different websites, which you’ll be able to kind of check towards one another to be sure you received the precise stuff.

All the way in which to the previous few days earlier than extraction they have been drilling, attempting to get the rock samples. However there was this second out on the ice, proper in the direction of after we kind of wrapped up, the place I bear in mind it felt unseasonably heat.

[CLIP: Sound of the members of the GreenDrill team around the Winkie Drill]

DelViscio: It was about 25 levels [F, or about –3.9 degrees C], which is balmy …

Feltman: Yeah.

DelViscio: On the ice sheet. And truthfully, the, the drill was simply, after going via a pair rounds the place it was robust going, kind of sliced like, you recognize, a knife via sizzling bread right down to the ice and received the rock out, they usually received this lovely lengthy core.

Caleb Walcott-George: Heavy!

Elliot Moravec: That there’s real rock core.

Walcott-George: Oh, child.

DelViscio: I simply bear in mind, Caleb Walcott-George, who was one of many scientists on the expedition, simply, like, hoisted it prefer it was, like, this prized bass.

Caleb Walcott-George holds up a rock core pulled from beneath the Greenland ice sheet in June 2024.

Jeffery DelViscio/Scientific American

Feltman: Yeah.

DelViscio: And there was kind of this shout throughout the camp.

Walcott-George: Oh, too late [laughs]!

Tanner Kuhl: I used to be simply baiting ya.

DelViscio: And once they closed the outlet they’d this liquor known as Gammel Dansk, which is that this Danish liqueur, however they name it “driller’s fluid.”

Moravec: There it’s.

Forest Harmon: You gotta lace it proper down within the casing, dude.

DelViscio: And so they poured one down the outlet to shut it out as a technique to kind of give the outlet one thing again.

Moravec: Bottoms up.

Walcott-George: You wanna see one thing I made?

Moravec: That’s all she wrote.

Kuhl: Nicely-done.

DelViscio: It was this actually clear end to what had been a fairly anxious couple weeks, simply attempting to get samples again with the window of time closing. So it was a, a pleasant second out on the ice and, you recognize, simply had music taking part in, and it felt like not the top of the world in the course of an ice sheet however a tight-knit science camp the place issues have been going proper.

Feltman: Yeah, that should’ve been actually cool ’trigger I really feel like there’s not a whole lot of subject work the place, whenever you get the factor you’re searching for, it’s, like, sturdy and hoistable [laughs], in order that’s enjoyable.

DelViscio: For certain.

Feltman: And I’m certain, you recognize, there’s gonna be years of follow-up analysis on this information, however what are they studying from their time within the subject?

DelViscio: They’d a, a web site in one other a part of Greenland from the 12 months earlier than the place they did the identical type of work, they usually’re simply on the level at the place they’re publishing that. And what it appears like is that there’s this place known as Prudhoe Dome, which is within the northwest a part of Greenland, the place there was this massive ice dome, and what these checks advised them was: it regarded very possible inside the Holocene, so within the final 10,000 years, that the ice was utterly gone there.

Feltman: Hmm.

DelViscio: And it was a whole lot of ice to remove that shortly. Once more, it’s, you recognize, you’re kind of going from this 2016 paper, which says one million years in the past it was ice-free—one million years is a very long time.

Feltman: Yeah.

DelViscio: However even a pattern in a spot the place there’s an entire lot of ice within the northwest of Greenland and having it gone inside the final 10,000 years, with weather conditions which might be near what we’re experiencing now, that places it on a “our risk” type of degree.

Feltman: Yeah.

DelViscio: As a result of in the end, you recognize, if the entire of the ice sheet melted, that’s 24 toes of sea-level rise. Which means huge migration, completely modifications the floor of the planet. However you don’t want 24 toes to actually mess some stuff up. So even 5 inches or 10 inches or a foot and a half is type of life-changing for coastal communities around the globe.

Each quantity of exactitude they will get on how this factor modifications, breaks up and melts is just a bit bit extra assist for humanity when it comes to planning for that type of state of affairs, which, given the state of our local weather, looks as if we’re gonna get extra soften earlier than we get it rising again, so it’s undoubtedly coming—the, the soften is coming; the flood is coming.

Feltman: Nicely, thanks a lot for approaching to share a few of your Greenland story with us, Jeff.

DelViscio: After all, I used to be completely happy to freeze my butt off to get this story for our readers and listeners [laughs].

[CLIP: Music]

The members of the GreenDrill expedition await subject extraction by airplane on the Greenland ice sheet in June 2024.

Jeffery DelViscio/Scientific American

Feltman: That’s all for at this time’s episode. Science Rapidly is produced by me, Rachel Feltman, together with Fonda Mwangi, Kelso Harper, Naeem Amarsy and Jeff DelViscio. This episode was edited and reported by Jeff DelViscio. You may take a look at his July/ August cowl story, “Greenland’s Frozen Secret,” on the web site now. We’ll put a hyperlink to it in our present notes, too.

Shayna Posses and Aaron Shattuck reality examine our present. Our theme music was composed by Dominic Smith. Particular because of the entire GreenDrill workforce, together with Allie Balter-Kennedy, Caleb Walcott-George, Joerg Schaefer, Jason Briner, Tanner Kuhl, Forest Harmon, Elliot Moravec, Matt Anfinson, Barbara Olga Hild, Arnar Pall Gíslason and Zoe Courville for all their insights and help within the subject.

Jeff’s reporting was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Middle and made doable via the help of the U.S. Nationwide Science Basis Workplace of Polar Applications.

For Science Rapidly, that is Rachel Feltman.

This story was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Middle. This story was made doable via the help of the U.S. Nationwide Science Basis Workplace of Polar Applications.

[ad_2]